Education Policy and Results: It’s (almost) All in the Implementation

Getting the right education policies into place is hard enough. But more often than not, implementation is where they fall apart. Let us share two striking findings. Find out!

May 2025 – by Carolina Rivas and David Evans*

Getting the right education policies into place is hard enough. But more often than not, implementation is where they fall apart. Let us share two striking findings. First, an analysis of more than 400 education policies across more than 40 education systems found that fewer than half of these policies showed evidence of progress or impact over the past decade. Second, another analysis of education policies found that even fewer demonstrated positive effects. A key factor contributing to this failure was a lack of effective implementation.

Even interventions that are initially successful often fall short at scale. One country had success hiring contract teachers who would be more accountable to their local communities. But the program was ineffective when scaled, in large part because its political forces meant that it couldn’t be scaled in the same way. Another example comes from early childhood development. A program in Jamaica to stimulate children’s development had enormous impacts: 30 years later, children in the program earned 37 percent more than a comparison group. When that same original program—which had just 70 children in it—was scaled up to 700+ children in Colombia and nearly 70,000 children in Peru, the effects were much smaller.

Recently, two organizations in Brazil—Fundação Bracell and Insper—ran a course for government policymakers on the effective implementation of education policies. In that context, we reflected on what drives good implementation.

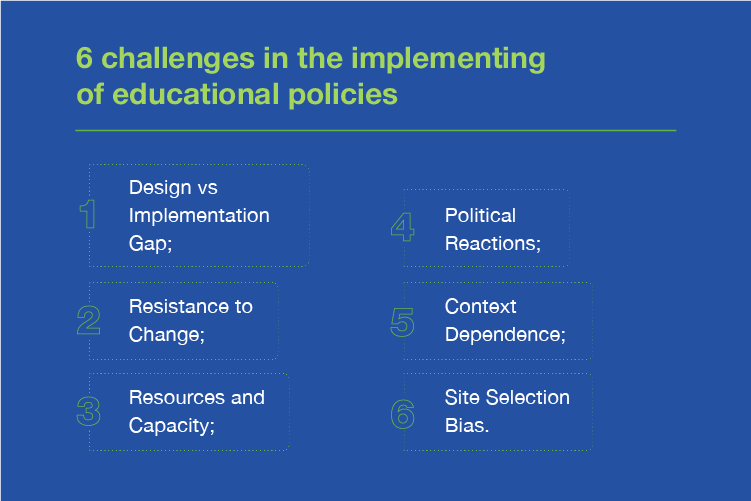

There are many reasons that education policies fail (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Six Challenges in Implementing Education Policies

Policies often receive a lot of attention during the design phase but much less during implementation. In some cases, key elements of implementation—like training of and support for implementers—are significantly reduced due to a lack of resources. Simpler interventions—those with fewer moving parts—may be easier to implement effectively at scale.

Stakeholders, including teachers, principals, and policymakers, may resist reforms due to conflicting interests, lack of understanding, or fear of change. When it comes to teacher policies, resistance may appear even when the changes could benefit teachers, for fear that accepting one reform might open the door to future, unwanted changes.

A lack of sufficient resources—both financial resources and human resources, limited expertise, and inconsistent institutional support can hinder successful policy implementation. Once Dave was speaking with a policymaker in a lower middle-income country, and she said, “Stop telling us what worked in Singapore!” The resources and capacity were simply too different for the examples to be useful.

Reforms can face strong opposition or shifts in political support, which may delay their implementation or reverse reforms altogether.

Policy success is highly dependent on context. Policies that work in one setting may not have the same impact in another due to differences in local conditions, resources, and the specific needs of the population. But remember that this doesn’t mean we can’t learn anything from successes and failures elsewhere: it means we have to be smart and humble about interpreting what we learn and adapting programs.

Systems often pilot interventions in places where the effects are likely to be particularly strong. For example, a scholarship program aimed at preventing school dropout may be highly effective in schools with the highest dropout rates. However, when scaled to schools with lower dropout rates, the effects may be significantly smaller.

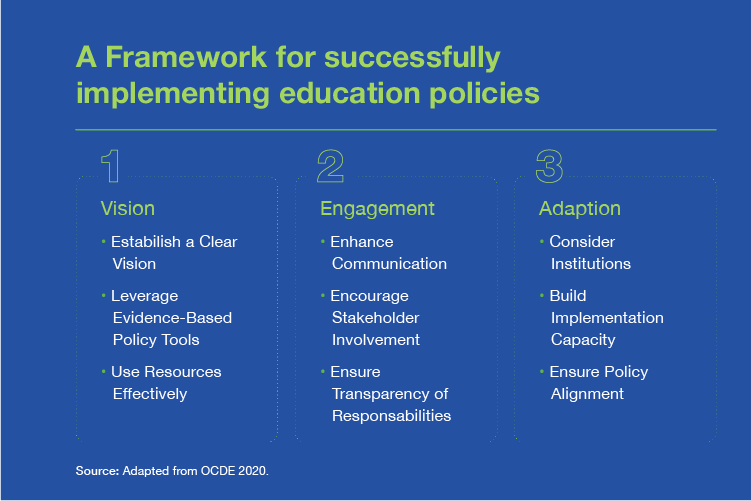

Okay, if that’s what makes things go wrong, how can education systems avoid these pitfalls? An OECD framework gives nine keys to success, organized into three axes: vision, engagement, and adaptation (Figure 2). Below, we discuss a few of these keys in more detail.

Figure 2. A Framework for Successfully Implementing Education Policies

The first axis is vision.

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Education has run a Best Evidence Synthesis Program to compile evidence on what works. A group within the ministry manages this program. They regularly publish reports, which are used by policymakers. An alternative model, outside the government, is the Education Endowment Foundation in the UK, which generates evidence on effective education policies and uses it to push for change.

The second axis is engagement. A key element of that is to enhance communication. Effective communication promotes mutual agreement, builds public support, and strengthens ownership of the policy. It should be a two-way process, conveying key messages while facilitating feedback from stakeholders. In Sobral, Brazil, the mayor pushing for reforms consistently turned to radio stations to discuss the need for change. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the secretary of education engaged in daily, two-way conversations with teachers over social media while implementing an ambitious program of educational reform.

The third axis of effective implementation is adaptation.

Guy Kawasaki famously wrote that “Ideas are easy. Implementation is hard.” Education professionals around the world face this every day. But if we avoid the pitfalls and stick to the principles of success, effective implementation of good education policies is possible, with great benefits for children and youth around the world.

*Article originally published in Enfoque Educação and translated into Portuguese by the Bracell Foundation team

01

Jul

Getting the right education policies into place is hard enough. But more often than not, implementation is where they fall apart. Let us share two striking findings. Find out!

23

Oct

The initiative, carried out in collaboration with the London School of Economics, aims to promote equity in Brazilian public health.

28

Jun

During the Bracell Foundation Symposium, the importance of strengthening public policies, developing leadership and investing in the comprehensive training of children was highlighted.